|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

'You're OK Kid' as seen in The Denver Post December 7, 1995 Written by Bill Briggs 'You're OK Kid' Reinhardts to take story coast to coast

He simply has no right to be here. No way he should be standing tall, charming a class full of teenage girls with his down-home ballad and defiant smile.

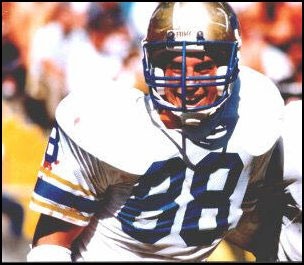

"Even if he pulls through," the doctors predicted, "it won't be Ed anymore." Well, hee-e-e-r-e's Ed!...Music Please. "Last night I dreamt I died and stood outside those pearly Gaaates. Suddenly, I realized there must be some mistaaake!" His voice boomed. His eyes sparkled. His words-from the song "A Father's Love"-rang eerily true. * * * For 62 days in 1984, Ed Reinhardt Jr. floated in the half-light between life and death. A blood vessel in his brain had burst during an apparently routine tackle late in a close football game. Just a week before, the University of Colorado tight end had set a school record by snaring 10 passes in one game.

Steady vigil His father Ed Reinhardt Sr.; his coach, Bill McCartney; and seemingly the entire state of Colorado maintained a steady vigil that autumn, searching for any signs, any real progress. His mother, Pat Reinhardt, prayed that Ed wouldn't die, then wrote his epitaph-"Farewell, Gallant Warrior." Slowly, gradually, Ed woke up. Like a new-born child, he couldn't walk, couldn't talk. Over the next several years, with his new coach-Pat-barking the signals, he learned to crawl again. First a few feet. Then an entire room. Soon, he was standing, stepping and later jogging. The Reinhardts built an addition onto their Littleton home and turned it into a padded rehab center. Exactly 140 friends volunteered to help out. Ed, who had been selected academic All-American while in a coma, soon remembered how to speak, to joke, to sing. Today, the right side of his 6-foot-7 frame remains in a stiff slumber, the remnant of damage to the left side of his brain. His speech is often reduced to one, two or three word bursts. His short-term memory is clouded. But Ed is there-sharp and funny, a once elite athelete now winking at this fresh but frustrating life. Over glasses of apple juice in the Reinhardt's kitchen. Pat raves about a new audio therapy they're trying. Ed, however, just twists a finger next to his head, rolls his eyes and says: "OK, Sure. Pretty good." And during a morning presentation at Arapahoe High School, Ed describes how double vision in his right eye makes reading a formidable task. "One-two all the time," he laments. "Chaps my hide." This is Ed's true vision-speaking to people about his comeback. Moving them. Infecting them with his spirit. He and his dad have made about 60 appearances together in the past two years. They talk to rotary clubs, service groups and schools to deliver a message that stretches beyond Ed Jr.'s courage to a deeper tale about the importance of families, particularly fathers. How does Ed, now 30, size up his new career? "Fun, Enjoyable. Enthusiasm." "He's been in front of Gayle Hayung's classes at Arapahoe High School several times, most recently to shoot the breeze with a dozen girls studying child development.

Croons a song After Ed croons a song or two, backed up by music from a small cassette player, the students watch a video of his CU days, including the injury and the recovery. Ed doesn't remember the hit or anything from the months before that game. He's seen footage of it dozens of times though. In the classroom, he watches it yet again with his hands gently clasped in front of this mouth. At the moment of impact on the tape, Ed drops his hands and moves backward slightly. Afterward, he asks the class, "What kind of questions?" "How long have you been singing," asks a girl in the back row. "Five years." "What do you do at Sandberg Elementary School(where Ed volunteers on Wednesdays)?" "Coach. Teach. P.E." "Do you miss being able to play football?" "Yeah," Ed says barely above a sigh. "Yes. Yes...(He pauses)...Yes." Later, one of the girls confides to Hayungs: "He almost brought me to tears." "Hey," the teacher fires back, "in years past when he sings this song, 'Thank God For The Children,' I started crying." It's all music to Ed Sr.'s ears. "He has a place to move and inspire a lot of people," he says of his son. And that's just what the Reinhardts plan to do. They want to elevate Ed's game. They want to take their son and their story into the limelight where father and son can speak to bigger audiences in bigger cities like Seattle and New York. For potentially bigger paydays. "We would like to move into this full time," Ed Sr. says. "I'm in sales. I'd like to phase that out and get into this...I'd be satisfied to go to Colorado Springs." Tomorrow, the Reinhardts go to Vail where they are scheduled to talk to folks at the Steadman-Hawkins Clinic.

Another Volunteer And he's doing it all for free. Yet another volunteer for the family. "I want to be No. 141 on the Reinhardt team," Sabah says. "These folks are just destined to impact the world." Says Ed Sr., "Certainly, for me and for Ed, the greater tragedy is if nothing comes out of this." * * * Tragedy in the Reinhardt clan goes back a couple of generations. It's a history of abandonment and divorce-a family slashed to pieces. That background really is the soul of the traveling father-son speeches. Their message is family not football. The Reinhardt story begins in a small watering hole in the sand hills of Nebraska. The year is 1938 and Ed Reinhardt Sr. and his father have paddled from the edge of a gravel pit out to a small island where father and son often built castles in the sand. They would play together until dusk, shaping stately palaces and swim back to shore with Ed Sr.'s arms draped tightly around his father's neck. "He always told me not to let go of him." Throughout his life, Ed Sr. never would. Several years later, his father left home to take a temporary job building a military base in Casper. But that job led to another position in the Aleutian Islands. Months turned into years. "All this time, I believed he would come home," Ed Sr. says. "I was too naive to think a man away from his kids five, six, seven years...was a problem." Ed Sr. was 19, his father 51 when the family gathered in a Eugene, Oregon courtroom to formally seek a divorce. After the hearing, Ed Sr. strolled around the University of Oregon campus-a place that would hold intense pain for the Reinhardts three decades later. The family had ice cream together for the first time at a little shop in Eugene. Then they all stepped onto the curb outside, at the corner of Broadway and Pearl Streets. "My father said, 'Goodbye.' He turned and walked one way and we walked the other. I was in the middle between my mother and my brother. We were all crying like we couldn't stand up. We turned around to look and my father was gone." The event hardened Ed Sr. He decided not to love anyone ever again to keep from getting hurt. He became profoundly independent, paying for a car and college education himself. He married Pat and they began a family. But Ed Sr. still felt incomplete. "I couldn't seem to get my life started until I got that mess(with my father) in some kind of order," he recalls. So, 15 years after the split, Ed Sr. began searching for his dad. He found him in the hills of Oregon, living on a ranch.

Reconciliation process "Hi dad," Ed Sr. said. "I'm your son. Do you remember me?" That encounter launched a long reconciliation process. Yet it took another seven years for father and son to move from talking about the weather to dissecting the anguish and anger Ed Sr. suffered from the abandonment. "I learned that my dad's father left when he was 3 or 4 years old...The things in our lives growing up we tend to recreate later on as adults because that's all we know." In the fall of 1984, Ed Sr. was about to continue the family legacy. He was on the verge of leaving his wife and six kids. "I'm thinking,'I'm no different from my dad. I'm named after him. I'm left-handed. Some say I look like him. I'm a maverick like him." On a sunny September Saturday, as his son prepared to play the University of Oregon in Eugene, Ed Sr. was quietly plotting how best to make the exit from his family. How and when. That day, Ed Sr. listened to the CU game on the radio, still buzzing about his son's week-old pass-catching record. Late in the fourth quarter, with Colorado trailing by a touchdown, Ed Jr. grabbed a short pass and ran to daylight. Two Oregon defenders grabbed the sophomore receiver. Ed fell. His head hit one of the defenders' thigh pads and then the turf. He wobbled to the bench and then collapsed. His brain was bleeding. His father was on a jet on the way out.

Instant replay It was a macabre instant replay. Ed Sr. was 51. His son, 19. Ed Sr. asked himself: "Why am I in Eugene, Oregon? Why did this accident happen here? It wasn't long before I began to see that the walls I had built up in this very town had to come down...I had people to love me and love them." He and Pat devoted their lives to helping their sick son get better. And Ed Sr. continued mending fences with his father. Five years ago, with his father getting on in years, Ed Sr. decided to go out and stay with his dad one last time. "I wanted to feel what it was like to go to sleep in the same house with my day just down the hall. "I remember that Sunday evening, after spending four or five days with him, I had to say goodbye. It was reminding me of that day in Oregon, saying goodbye on the street. As we moved closer to the door that evening, I remember leaning over and giving him a big hug." "I love you dad," he told him. "I've always loved you." "You're OK kid," his dad replied. It became Ed Sr.'s mantra. It embodies the advice he and his son now impart to their audiences. "He didn't tell me I was a good worker or a good father. He told me that from head to toe I was OK...There were no conditions. "How important that is to hear that from our fathers," Ed Sr. says. "If every father could get up with their children and tell them they're OK, what a difference I believe that could make." "You're OK, Kid," Ed Jr. repeats. Two months after his own father died, Ed Sr. told his story to a Boulder prayer group hosted by Bill McCartney. Ed Jr. came along to sing a song for his former coach. (The Reinhardts are a deeply religious family. Ed and his mom often speak at churches). But that event marked the father and son's first presentation together. As they left the prayer meeting, McCartney caught up with them. "You know," he said, "men need to hear this." * * * Back at Arapahoe High School, just a few miles from their home, the Reinhardts deliver the heart of their message. "Men (are) told that we're macho, that we don't show our feelings and that our communications are minimal," Ed Sr. says. "Do we avoid relationships because we fear rejection? Go ahead. Take the risk. Try again. Break the cycle..." "Tell your parents you love them." The bell rings. Ed Jr. gives high fives to the students as they stroll out of the classroom. Later, he and his father walk together through the school. Outside, Ed Sr. gets into the drivers' seat of his car and his son slowly maneuvers into the passenger side. They drive off side by side. The morning sunlight reflects off the rear license plate. It reads: UROKKID.

|

||

|